This interesting paper by Srivastava, Greff and Schmidhuber (arxiv) looks at the problem of enabling deeper architectures for neural networks. The main argument being that Neural Networks have become successful mainly because training deeper architectures has only recently become possible – and making them deeper might only improve performance. However, performance tends to plateau in conventional deep architectures, as exemplified by their first plot.

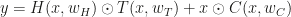

The proposed solution to training deeper architectures is to simply introduce a gaiting architecture similar to LSTM ideas. If a normal layer is defined by  for output y, input x and parametrization of the layer given by w, a highway layer is simply given by

for output y, input x and parametrization of the layer given by w, a highway layer is simply given by  , where T and C (Transfer and Carry, respectively) are functions with a (co)domain of the same dimensionality as x and y. This is called a highway layer, as gradient infomation supposedly travels faster along the $latexx \odot C(x, w_C)$ part (hence the Autobahn illustration). When it is required to change dimensionality, one has to resort to a normal layer, or subsample/pad.

, where T and C (Transfer and Carry, respectively) are functions with a (co)domain of the same dimensionality as x and y. This is called a highway layer, as gradient infomation supposedly travels faster along the $latexx \odot C(x, w_C)$ part (hence the Autobahn illustration). When it is required to change dimensionality, one has to resort to a normal layer, or subsample/pad.

Now this archictecture of the highway layer of course allows for gradient information in SGD to travel two paths, one trough  , one through

, one through  and the output of a layer is a combination of the input of the layer x and the output of

and the output of a layer is a combination of the input of the layer x and the output of  . The authors use a logistic model

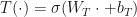

. The authors use a logistic model  and

and  . The authors biased towards simply carrying information through without transformation, which in their setup means simply

. The authors biased towards simply carrying information through without transformation, which in their setup means simply  . After training the network with SGD an looking at the value of the transform gates of different layers, they find that those are closed on average (Figure 2, second column) while exhibiting large variance across inputs (exemplified by the transform gate outputs of a single sample, Figure 2, third column). Interestingly, some dimensions of the input to the network are carried through right to the last layer.

. After training the network with SGD an looking at the value of the transform gates of different layers, they find that those are closed on average (Figure 2, second column) while exhibiting large variance across inputs (exemplified by the transform gate outputs of a single sample, Figure 2, third column). Interestingly, some dimensions of the input to the network are carried through right to the last layer.

They find that this architecture not only helps to train larger networks, but also aids actually utilizing deeper architectures. So this paper took a similar inception as LSTMs: tries to solve an inference problem and comes up with a model that is more powerful in a way.

I feel that the result is somehow odd: carrying the input information through can be achieved by setting the weights in the original normal layer  accordingly (if it is fully connected that is). Why does adding the extra complexity gain so much? I do not feel the paper addressing this important question and I can only speculate myself: perhaps the transform/carry architecture is effective because its weights lie on a compact manifold (because of the logistic transform). Maybe the problem becomes better conditioned because simple downscaling of the input is done by T, while H takes care of actual transformations. To check this, it would have been interesting to know whether they used any constraints on the weights of H – if they haven’t, and H is fully connected, the better conditioning might be an actual explanation. In that case, simply constraining the weights

accordingly (if it is fully connected that is). Why does adding the extra complexity gain so much? I do not feel the paper addressing this important question and I can only speculate myself: perhaps the transform/carry architecture is effective because its weights lie on a compact manifold (because of the logistic transform). Maybe the problem becomes better conditioned because simple downscaling of the input is done by T, while H takes care of actual transformations. To check this, it would have been interesting to know whether they used any constraints on the weights of H – if they haven’t, and H is fully connected, the better conditioning might be an actual explanation. In that case, simply constraining the weights  of H (mapping input

of H (mapping input  to the same output dimension

to the same output dimension  ) in an appropriate way might have similar effects.

) in an appropriate way might have similar effects.

EDIT: After talking to the authors, I realized where my thinking was insufficient: the layer H inside the highway always used a nonlinear map. The gating allowed to switch that off. I guess thats the difference from reading about NNs to using them…

is the joint probability of the actual sampling space you care about (the marginal being the target distribution/posterior) and possible auxiliary variables. Now they suggest parameterizing f by one skew-symmetric and one PSD matrix (both of which can depend on the current state z), and proof in two Theorems that this is all you need to describe all Markov chains that admit the target distribution as the unique stationary distribution. The proofs use the Fokker-Planck and Liouville equations, which as a non-SDE person I’ve never heard of.